A few months ago, our hospital's Disaster Preparedness Team ran a simulation in our emergency department. The incident involved a so-called "dirty bomb" that was set-off during a large summer music festival and involved multiple casualties. Oh, and by the way, during the event the hospital experienced a power outage. When I first heard about the scenario, I shook my head and said, "Boy, I hope that never really happens!" It was just like the author Lemony Snicket's "Series of Unfortunate Events". Notably, Snicket once said that "Imagining the worst doesn't keep it from happening." He of all people would certainly know, even though his books are entirely fictional. While I completely agree with him, I can't think of a better way to be prepared for an unfortunate event than imagining the worst beforehand.

I've been talking about Barry Turner's "Man-Made Disaster Model" as presented in his 1978 book, Man-Made Disasters. Turner posthumously published a revision of the book with Nick Pidgeon in 1997. One of his most important contributions to the safety science literature is the concept that man-made disasters develop over a long period of time, during the so-called "incubation period." I discussed his model at length in my first post, "The Failure of Foresight". His model was based on an analysis of 84 British accident inquiry reports covering a 10-year period of time, though he focused on three events in particular (covered in my second post, "It takes hard work to create chaos!"). As mentioned in my last post, I would like to move now to a brief discussion on some of the interventions that can help prepare organizations to prevent or at least mitigate man-made disasters.

I would like to focus on two excellent articles written by Turner's co-writer in the most recent edition of his book, Nick Pidgeon. The first article was published in the Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, "The Limits to Safety? Culture, Politics, Learning and Man-made Disasters", while the second article was published in the journal Safety Science, "Man-made disasters: Why technology and organizations (sometimes) fail". Both articles speak to the importance of "safety culture" in an organization. If organizational culture is defined (very loosely) as "the way we do things around here", then "safety culture" may be similarly defined as "the way we ensure safe operations around here." However, a more formal definition comes from the Advisory Committee on the Safety of Nuclear Installations (ACSNI) Human Factors Study Group's third report on "Organizing for Safety" which states:

"The safety culture of an organization is the product of individual and group values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and patterns of behavior that determine the commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, an organization’s health and safety management. Organizations with a positive safety culture are characterized by communications founded on mutual trust, by shared perceptions of the importance of safety and by confidence in the efficacy of preventive measures."

Pidgeon suggests that a positive safety culture is characterized by four components, most of which are consistent with the defining characteristics of so-called High Reliability Organizations (HROs). HROs HROs are usually defined as organizations that somehow avoid man-made disasters (to use Turner's term), even though they normally exist in an environment where normal accidents can be expected to occur by virtue of the complexity of the organization and by the nature of the industry. Here are the four components:

1. Senior management commitment to safety (see my recent post, "Be the best at getting better")

2. Shared care and concern for hazards (for more, see "Preoccupation with Failure")

3. Realistic and flexible norms and rules about hazards (see "Commitment to Resilience")

4. Continual reflection upon practice through monitoring, analysis, and feedback systems (see "Sensitivity to Operations")

Importantly, while a commitment from senior leaders (top-down) is absolutely essential to building a positive safety culture, culture has to be built from the bottom-up. As Turner himself stated, "Managers cannot simply 'install' a culture...viewing safety culture as a continuing debate makes it clear that it is a process and not a thing..."

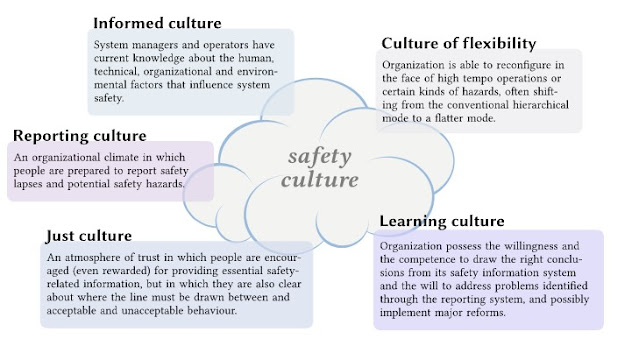

James Reason (who developed the Swiss Cheese model of error) suggested that a positive safety culture consists of the following sub-dimensions:

Pidgeon emphasizes the importance of organizational learning, even suggesting that "permanent culture change may itself be best approached through processes of long-term organizational learning or 'self-design' rather than solely through management edict (decree) or imposition of external regulation (prescription)." To build upon the quote by Lemony Snicket above (though I don't know if Pidgeon ever read "Series of Unfortunate Events"), Pidgeon suggests that a process of "safety imagination" can help overcome some of the organizational barriers to learning. He writes, "The idea of safety imagination is based upon the principle that our understanding and analysis of events should not become overly fixed within prescribed patterns of thinking, particularly when faced with an ill-structured incubation period."

In both articles, Pidgeon shows a table that was derived from a set of teaching programs developed over several years by the U.S. Forestry Service to help train fire-fighters. Here are his "guidelines for fostering safety imagination":

1. Attempt to fear the worst (recall that one of the barriers discussed by Turner was a tendency to minimize emergent danger)

2. Use good meeting management techniques to elicit varied viewpoints

3. Play the 'what if' game with potential hazards

4. Allow no worst case situation to go unnoticed

5. Suspend assumptions about how the safety task was completed in the past

6. Approaching the edge of a safety issue a tolerance of ambiguity will be required, as newly emerging safety issues will never be clear

7. Force yourself to visualize 'near-miss' situations developing into accidents

Safety imagination is a process of creating your very own version of a "Series of Unfortunate Events". Just like the disaster scenario that our hospital conducted, imagining the worst possible chain of events is one of the best ways to prepare an organization for man-made disasters. Safety imagination, as an exercise, will help extend the scope of potential scenarios that an organization could possibly face, counter complacency and the view that "it can't happen to us", force the recognition that during the incubation period, the most dangerous and ill-structured hazards are often ambiguous and withheld from view, and perhaps most importantly, suspend institutionally defined assumptions about what the likely hazards an organization will face.

I've learned a lot by reading both The Logic of Failure by Dietrich Dörner and Man-Made Disasters by Barry Turner. I can certainly see why they are classics in the safety science literature. The information that these two books covered is foundational, in my opinion, for any organization that wishes to become a High Reliability Organization.

No comments:

Post a Comment